Eerder in de spotlight

Zoek in ons archief op

naam, trefwoord of datum:

Marcos Kueh: “I feel privileged to have a space for expression.”

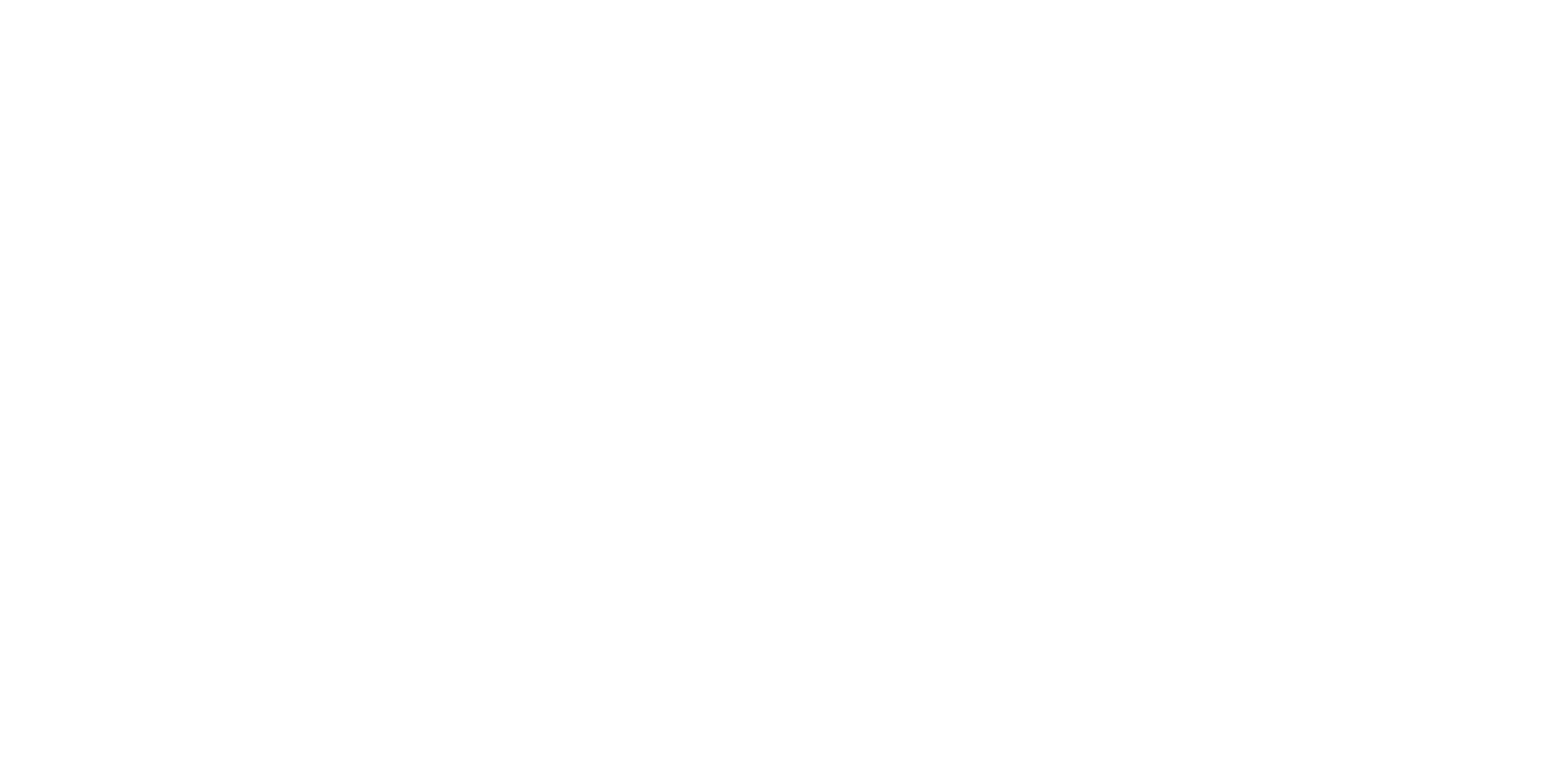

Meet Marcos Kueh, a textile artist from the island of Borneo, with a background in graphic design and advertising. Kueh's giant woven posters are colourful, and include subtle encrypted messages for the attentive viewer, just like the weaving of his ancestors contained their myths and stories. The 29-year-old artist, who combines traditional weaving techniques with industrial processes, has been exhibited widely, from the Stedelijk Museum and the Museum Voorlinden, to the Back Room in Kuala Lumpur.

In the following conversation, we reflect specifically on the contemplative texts that Kueh shares online, in which he suggests a point of view on his work.

By Anna Swagerman

How do you usually start your interviews, shall I just introduce myself?

Yes, go for it!

“Well, I'm originally from the Sarawak part of the island of Borneo. At the moment I’m very involved in contemporary art, but if you were to ask me to define myself, I’d say I'm just always open to seeing what’s out there. Whatever comes my way, I’m curious to try it. Apart from being an artist, I'm also just a non-European trying to survive in Europe. My background is in graphic design and advertising, but when I was studying at the art academy in The Hague, I got involved in the textile department and never looked back.”

I’m really intrigued by the texts you publish online to illustrate your textile work. For example, the story about the tigers, connected to your work “No tigers in Borneo (2024)”:

“They told us not to head into the rainforests because the tigers might devour you, but what is scarier, I think is the death of trust and belonging when you find out that your identity is actually just a myth...I wonder how many of us are sitting still, petrified to head out into the wilds, because we believed in false values.”

This text reminds me about the importance of deconditioning, especially for creatives searching for true expression. Have you always been able to express yourself well?

“These are interesting observations. I like to reflect on my writing because I don’t usually talk about it very much. Learning to express myself, coming from a developing country, is relatively new for me. When I studied graphic design in Malaysia, the focus was on production and speed. Working with Photoshop, Illustrator and so on. We were not really taught how to express ourselves. It was only when I started learning English that I began to pick up on some important terms. For example, I didn’t learn the word decolonization until I was 26, and now I’m 29, so a lot of concepts are still very new to me! But I feel it all happened at the right time. If you had asked me to express myself when I was 18, I wouldn’t have felt confident enough. Now I can speak in a way that I’m able to stand by. My expression happened sequentially: first I learned a craft, and then I had a platform and learned to speak up. I don't think there's a lack of opportunities for people to express themselves nowadays because of social media, but to craft what you want to say, it takes time and mastery. I think my sensitivity to communication comes from my training as a graphic designer. It taught me to be mindful of the content we create and consume.”

“There should be space for expression that is

more for the introverted, for the shy.”

Your work discusses important activist issues such as decolonization, but you’ve chosen a style of communication that is full of nuance and humor.

“Yes, that’s true. I belief that in the Western world there are not enough examples of how we can slowly develop and moderate our expression. If some people want their content to be very expressive and bold, that’s fine, but at the same time, there should be space for expression that is more for the introverted, for the shy. When we talk about inclusivity and having a diverse environment, it also means that there should be spaces for different types of personalities to exist. There's always a stereotype that Asians are shy about expressing themselves. But instead of telling Asians to express themselves more like Westerners, the alternative is to consider that there are ways to develop what they already are. Because the fact that people are compliant, doesn't mean that they’re not intellectual or sophisticated inside. If you look at the current industry, I am very critical of the way we express things nowadays.”

Another of your texts that caught my eye was the one you wrote in relation to your work “Expecting (2023)”:

“In our current political climate, it seems like there are so many loud, uncomfortable, confusing emotions that we need to eject them immediately out of our systems through expressions. I wonder what the world would be like if there are more spaces for us to feel safe to sit with silence and just grief – from the small things to the impossible.”

This text made me think about your experience of weaving, which is a long process, not a quick expression.

“Yes, you’re right, there are quicker mediums than weaving, which are more advantageous in the society we're in now. But that doesn't mean that the slower media are less meaningful. We have to be aware of the costs of doing things at high speed. For example, printing is much faster. But if you print 500 flyers and hand them out, people will take a quick look at the content and then throw them away. But with the medium of weaving, the viewer manages the content in a more considerate way: they can actually re-consider it. When I was training to be a graphic designer for the advertising industry, it was all about reducing concepts into a short sentence, because we only have three seconds to get people’s attention. We’ve become this society that’s always trying to rush, and our emotions can't pick up that fast. If we’re putting out so much content and being so productive, we should realize that we’re inviting the same amount of problems. We don't have enough time to process it all. It’s actually quite aggressive. Whatever you put out into the world, it always comes back with the same mindset. Another good example is fast fashion. It’s a subject I'm very interested in. In the society we’re in at the moment, there’s still this hierarchical view that something is less useful if it’s less productive. But I think that's something we can reconsider.”

How does expressing yourself as an artist compare to expressing yourself as a designer for you?

“For me, working as an artist comes with a lot more responsibility than I was used to as a designer. To express yourself is very cringy, because the art critics are intense nowadays. As a designer, it was easier for me to hide and say I was doing something because the client wanted it. Now it’s nobody’s fault but my own. I’m trying to be as gentle and responsible as I can be. I educate myself enough so that when I put content out into the world, it's mindful, and I hope it spreads some positivity. What I express is of course not an ultimate truth, and knowing that helps me a lot. I'm saying this because in the society we live in at the moment, people seem to be constantly thinking that they have to defend their truth and so much energy is spent on that. It creates a lot of conflict when everyone is trying to be right. I think it’s just a matter of having a space to express yourself, knowing that you don't know it all, and having grace for other people. Understanding where each of us comes from and that the things we express aren’t always right.”

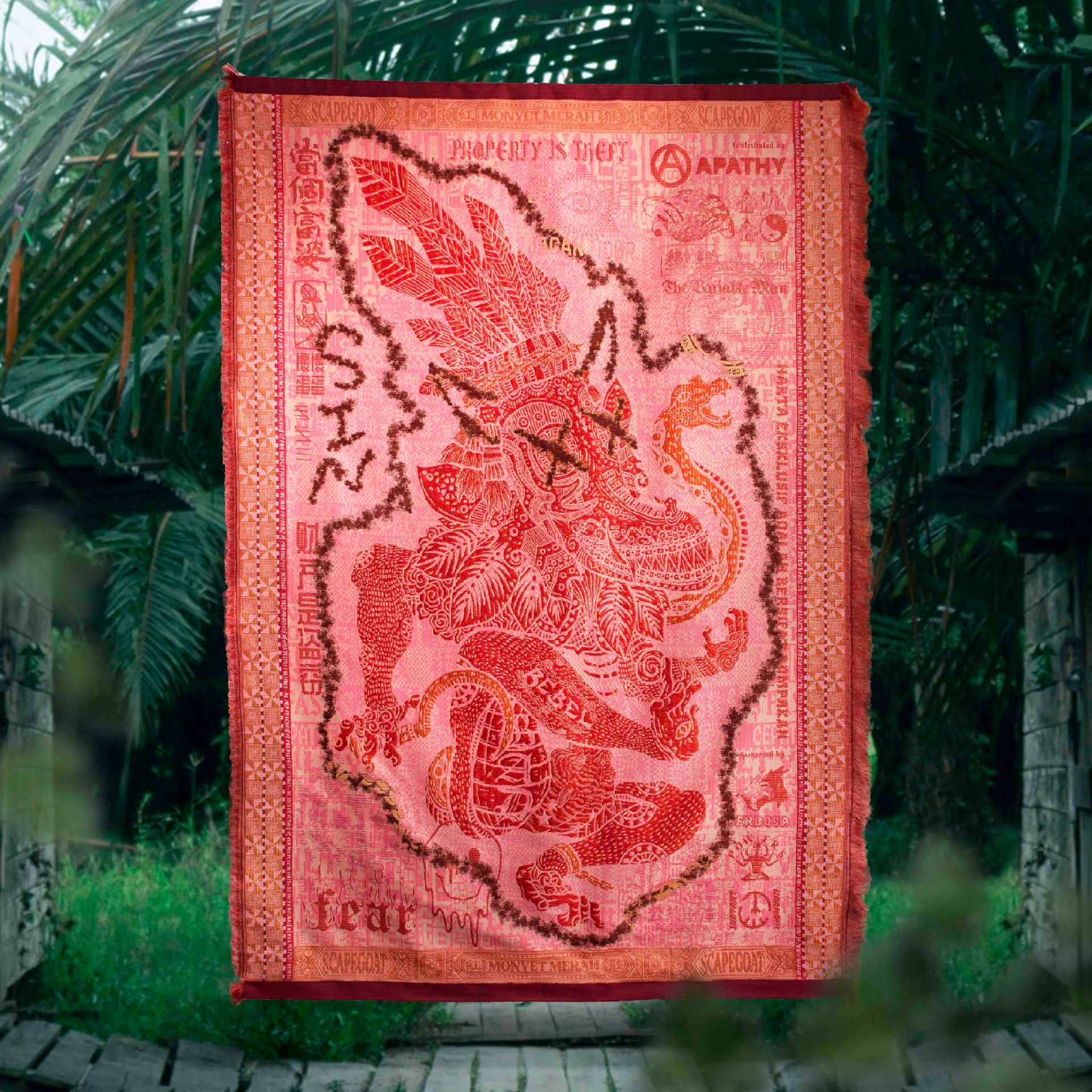

This tolerance makes me think of another text that accompanies your artwork “The Scapegoat (2023)”, which talks about a personal experience you had in high school.

“…one of my school bullies, Nigel, would always show up on Sunday afternoons in the middle of town. He would travel from table to table, café to café to ask if anyone was interested to buy cakes that his mom made. Usually customers would just politely say no but once I saw Nigel getting shouted at and shamed publicly for interrupting customers during their meal times. Since that day I constantly wondered when Nigel threatened to bully in school, if it’s just the way he copes with everything. Is it weird to say that I didn’t really mind being the scapegoat for Nigel for a while? I mean if it’s all systemic and not personal I can share some weight being pushed around for a bit – to understand a bit of suffering before I grow too blind of it.”

“I like that you brought up this text. I encounter this kind of situations less and less, because we're so much in our own world at the moment. I don't go out like I used to in my hometown. If you're in a small town, and you sit down, you see the same people with the same stories and dramas. Nowadays, you can almost distance yourself from the problems. We live in a society where people move around a lot more. Experiences are more sterile in a way.”

When we talk about tolerance in today's society, how do you see the role of artists?

“I think nowadays we’re very attached to the idea that artists or designers should be saving the world with their work, but we also need the support of the public. I think the responsibility is not only on the side of the artist who expresses something, but also on the side of the public to be kind and generous in their feedback. I’m cultivating that type of relationship with my audience. There are also artists who live more in their own world and don’t think as much about how people are going to receive it, but I like to keep the audience in mind, because I want to speak to the public in some way. I feel that in the art world the expression is becoming very curated, and it’s harder for people nowadays to be brave and try things out. I think it was different for the older generation.”

“It would be very special for people back home

to have a space to reflect on important issues.”

Is it important to you that the people in your home country are able to visit your exhibitions?

“Yes, it’s one of my long-term goals at the moment to plan for more shows in South East Asia. I have already done a show in Singapore because I like the idea of developing projects together within my region. I find it important to have conversations with people from my hometown, because I feel privileged to have a space for expression now. It would be very special for people back home to have a space to reflect on important issues. It can challenge them to think about who they are and how they want to be in this world.”

Did your relationship with people close to you change because you express certain narratives about your homeland?

“No, I try to keep my profession strictly separate. When I'm at home, I'm just my parents' son and that's it. We enjoy food together. My work is a very idealized version of my values. I express things that a great human being would say, but I also still like to do capitalistic things. I like to go shopping. It’s actually in these mundane activities that I find stories that people can relate to. If you isolate yourself from society, the stories become unrelatable. I also have mixed feelings about fame in the art world. The attention should be on my work, I don’t want it to affect my life. Also, I think human beings were not always as individualistic as we are now. We used to function more as a part of the whole. I think it gives some comfort when we remember that. But it’s a long process.”

It reminds me of the text you wrote about the sun.

“The other day I was contemplating on being the sun. How wonderful is it that the Sun just does its own thing – reliably running its responsibilities, on time when it rises and sets strictly on schedule – that’s discipline. I wish sometimes that I were more like the sun. I guess 27 years is not too late to have new goals and values in life.”

“Yes, I wrote it when I was trying to get used to life as an artist. You have to be consistent and make sure you shine. Because at some point it’s going to be winter. I make plans for the goals that I want to achieve, but it happens also quite organic. If there are important events, I try my best to be there. Because I think people remember people. It’s not just about what you make. This also makes the work a more human experience. I hope I don’t lose that.”

Your work intersects between art and design. Do you think these disciplines will merge more in the future?

“This was a question that the education departments were also trying to figure out when I was a student. A lot of graphic design is now used to serve capitalist jobs. I don’t think that capitalism is bad in itself and that design should stop serving it, because if we were to completely reject capitalism right now, there would be an identity crisis that I don't see a solution to yet. I’m trying to actively engage with people in the design industry, because even though I’m more involved in arts now, I think design is a wonderful industry. When I worked as a designer, I enjoyed the feeling of making people’s business more beautiful. Imagine a woman who cooks curry and wants to express some warmth through her food. I find it very meaningful to help her communicate that message. When you scale these things up, it tends to get a bit more complicated, but there’s still a beautiful core value that we can put forward. I think the industry just needs to rediscover what is meaningful to them.”

“If you go through doubts, crisis and chaos,

it means that new and weird things can happen.”

You’ve ventured out from graphic design to working with textiles. What would you say to other designers who would like to take the plunge and look outside of their area of expertise?

“I think it’s important to realize that an identity crisis is also a great opportunity. If you have it all planned out, then nothing new is going to happen. You're just going to get a job in a design agency when you graduate and that's going to be your life. But if you go through doubts, crisis and chaos, it means that new and weird things can happen. It’s uncomfortable to go through that space of uncertainty, but the fact that it’s uncomfortable doesn't mean it's bad. It takes courage to be okay with uncertainty.”

You live in The Hague, and your studio is in Rotterdam. How do you experience working in Rotterdam?

“Rotterdam was the first European city I came to when I was 21 years old, so I feel a special connection to this city. The people here are energetic and vibrant. When I came to Rotterdam, I did an internship at studio Dumbar.”

Thank you very much for this interesting conversation. Is there anything you’d like to mention that we haven’t covered yet?

“I enjoyed this interview because we were talking about my writing, which is very specific. I don’t include my writing in the exhibitions because I want people to look at the work in their own way. But with the texts that I share online, I’m suggesting a point of view. It was also good to talk about design, and I think it's important that you have these conversations. The design industry needs some love and the attention at the moment, because we’re all going through some crisis.”

Upcoming events: From September Marcos will be participating in

GLUE Amsterdam

(September 19-22) and

Manifesta 15 in Barcelona Metropolitana

(September 8- November 24).