Nu in de spotlight

Zoek in ons archief op

naam, trefwoord of datum:

Nobuhiro Shimura: “I allow myself to focus on the small details”

Meet

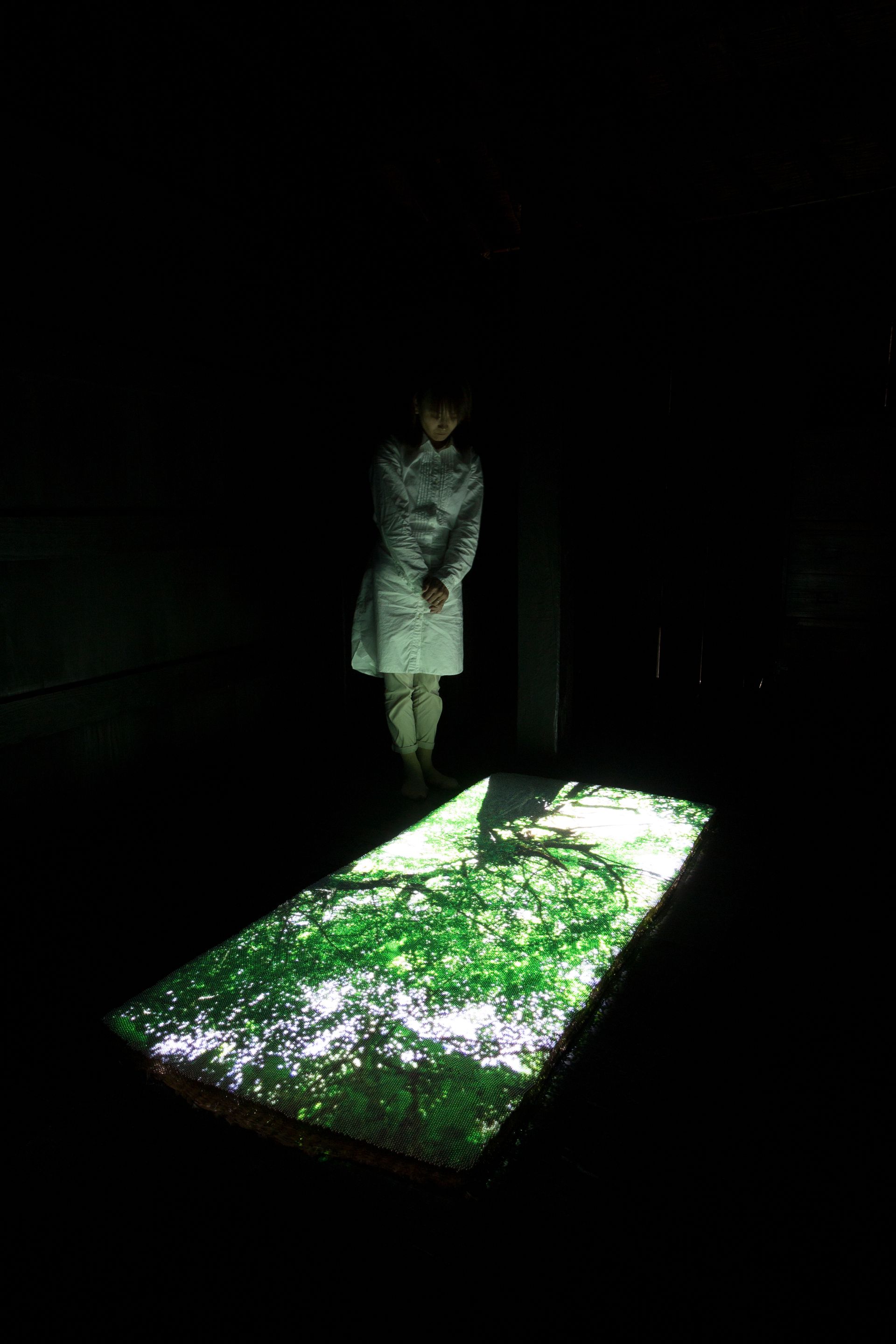

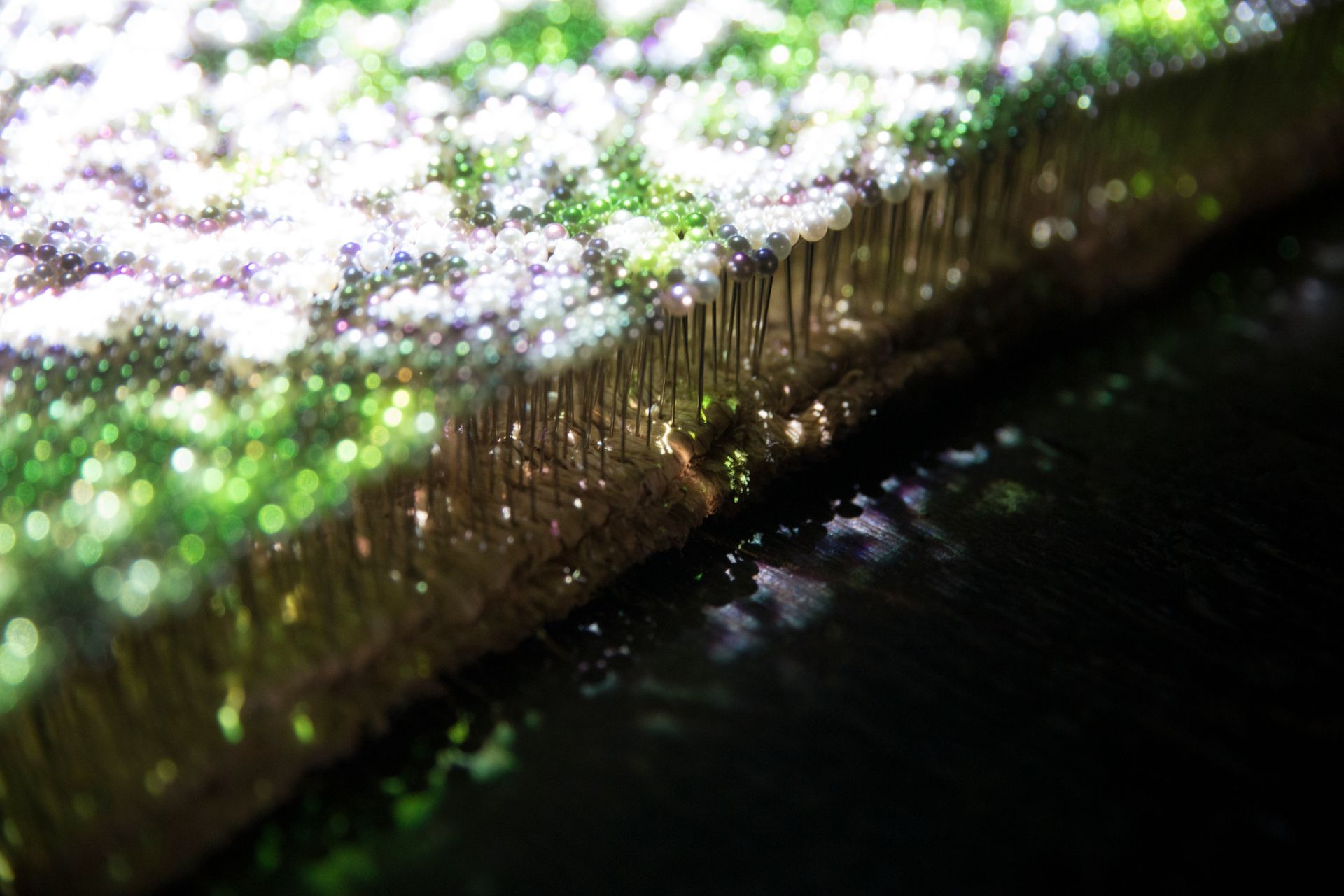

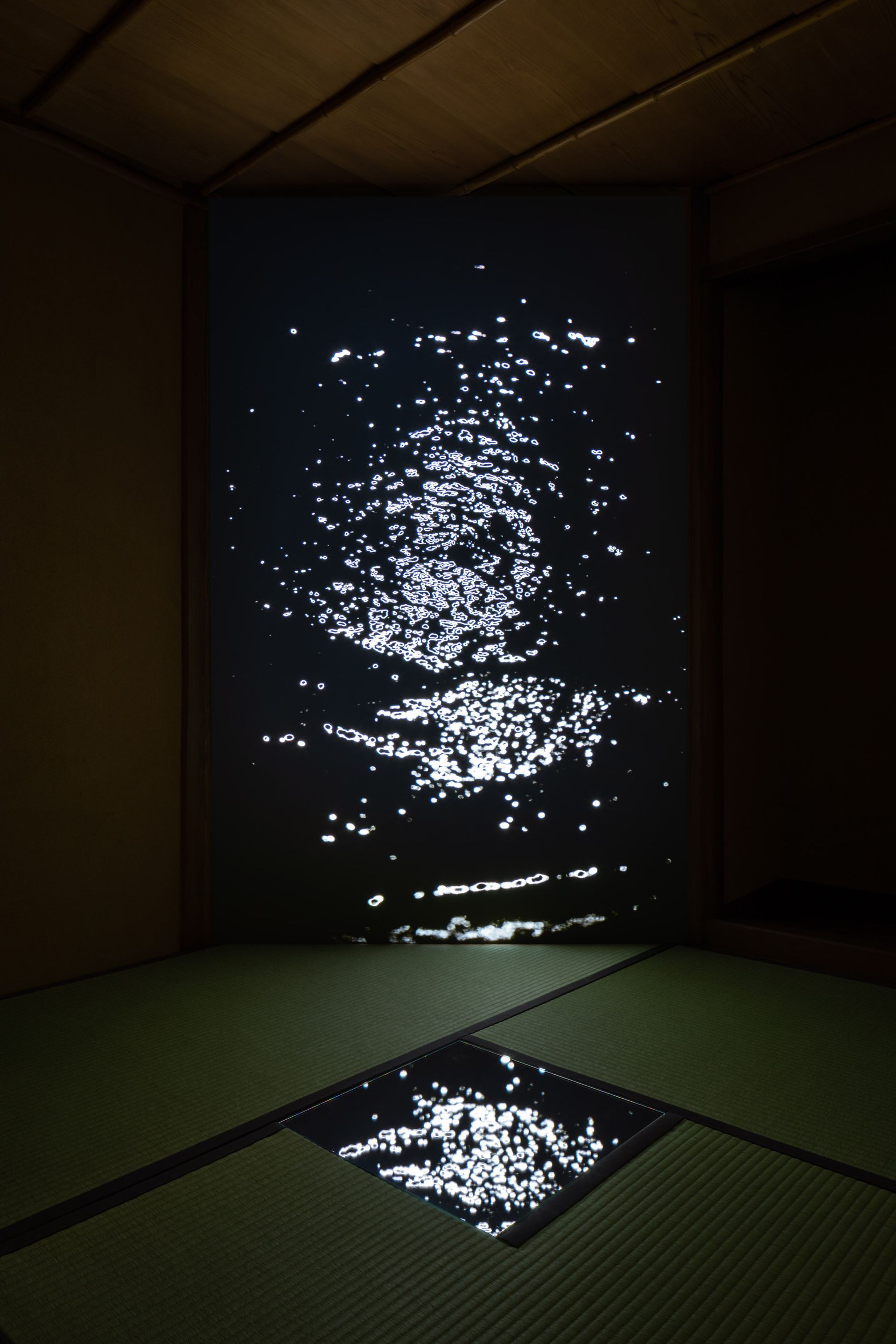

Nobuhiro Shimura (1982), a Tokyo-born artist who creates video installations incorporating documentary techniques. Shimura’s meticulous fieldwork is focused on the memories of people and places at risk of being forgotten. His installations frame everyday objects and occurrences as significant, drawing inspiration from conversations with local communities and his own observations. Nobuhiro’s video projection

Beads has been shown at the Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama, Japan (2024) and his film

Afternote

is currently on display at the Japan Foundation in Sydney, Australia. In the following conversation, Shimura shares his thought processes and introduces some of his recent projects.

By Anna Swagerman

You work with moving images. Can you remember how you came to this choice?

My point of departure was the medium of moving images, but I never had a clear idea of where that would lead me. Over time, I began to realize that I find it important to use real images of existing objects, instead of for example, computer graphics. For me, this is a way to strengthen the relationship between the everyday and the extraordinary. Many things might not seem special at first glance, but by enlarging them, I suggest seeing them in a different light. It is a way to enter into an abstract dialogue by using concrete things. The fact that I can do that with video—it’s not a small thing. It has grown to mean a lot to me.

Can you describe a recent project where you used this approach to see something in a different light?

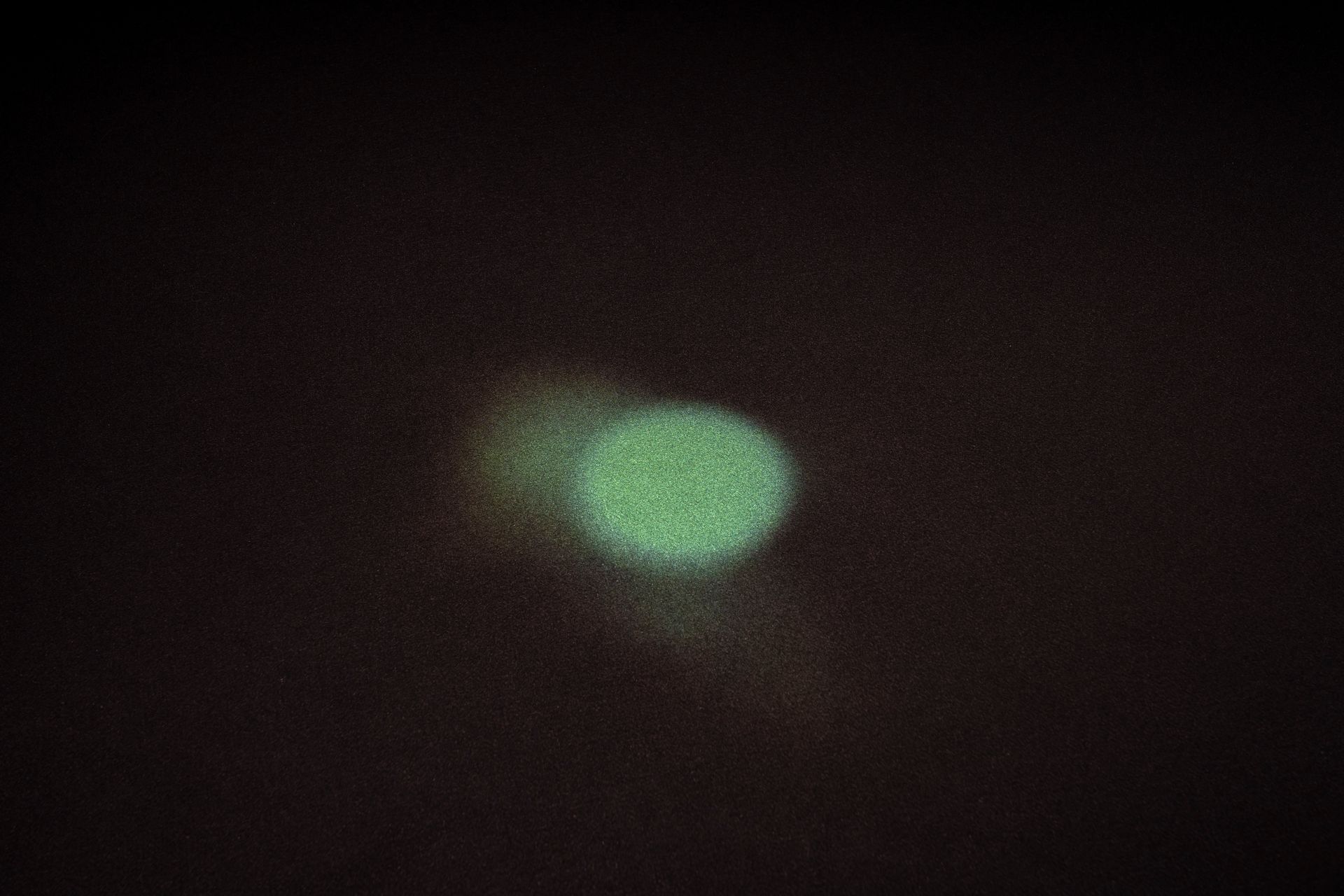

A good example is my installation

Tender Moon. During the pandemic, when it was difficult to work with other people, I shifted my focus to something else. Every month, during the full moon, I went out to take photos and film. Over time, I began to appreciate the fact that what we see of the moon is merely a reflection. It doesn’t shine; its light is reflected. The sun emits light, similar to a monitor, but the moon is more comparable to a reflector. Perhaps that’s why I’ve developed a sense of sympathy for the moon. It became a metaphor for the moving image for me.

You like to ponder the essence of the moving image. What makes this medium so interesting to you, compared to other forms of expression?

One of the most intriguing aspects of the moving image is that it has no inherent weight or form. In a way, when we look at it, we are seeing something that we don’t truly 'see.'

“The projector has the ability to enlarge things,

which fascinates me.”

A moving image requires a projector to come to life, and the projector has the ability to enlarge things, which fascinates me. What intrigues me most is that you can project onto almost anything, not just conventional screens. For example, I’ve experimented with projecting onto buildings and even onto a field of pinheads from thousands of pins arranged on a tatami floor. Displaying my images on a monitor is something I don't find aesthetically appealing. What helped me think more deeply about the world of moving images and film was my experience working as a projectionist for several years, at the

Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM)

in Japan. This experience was very important to me, as before that, I had only worked with digital images."

How did the idea that a moving image has no form of itself inspire your work?

My earlier mentioned work

Tender Moon

is a direct example of this. It shows a light reflection of the moon on the wet sand of the shore. But this reflection is also the moon’s shadow at the same time. Given the fact that the moon doesn’t shine on its own, it can become confusing to discern what we are really looking at. I like that confusion.

“It exists here for me, but it also exists there for you.”

The moon has been a source of inspiration for so many artists, especially in Japanese culture. I believe there is something timeless about the moon. It exists here for me, but it also exists there for you. That sounds like a simple fact, but it is not to be taken lightly. Sometimes I wonder what the first moving image must have been for human beings. One of the earliest experiences, I think, was watching the reflection of the moon or the sun on the surface of water. The fact that Tender Moon shows an image that has already been witnessed by people centuries ago is something I truly appreciate.

Another source of inspiration for your projects comes from working with the memory of things that are on the verge of being forgotten. Can you tell us more about that?

Yes, I like the idea that an artist can suggest small corrections to history. As generations pass, certain stories can be entirely forgotten. I believe an artist can address these gaps in a way that is different from how a journalist might. For instance, when people want to learn about the history of a place, they can visit a library, where countless books written by professors, researchers, journalists, or government officials provide extensive information. These works strive to be as objective as possible, but they are never perfect, and some memories or pieces of history can still slip through the cracks. As an artist, I allow myself the freedom to focus on the small, often overlooked details, which can reveal universal stories that might otherwise remain hidden. In this way, I feel I can serve a meaningful purpose. For example, my work about cattle is now part of the collection at the

Yamaguchi Prefectural Art Museum

in Japan. This recognition affirms that the stories I explore have value not only for me but also for others.

Can you tell us more about your work on cattle and the value of it?

The power of animals has become a topic very dear to me. I found out that on the island of Mishima (Japan), the cattle is on the verge of extinction. Cattle used to be a means of transportation and farming on the island, but because of lifestyle changes, cars and tractors replaced this.

“Listening intently to the small voices, universal stories

can come to the surface.”

Farmers living on the island have deep memories related to cattle, which I find very interesting. With a Super 8 camera, I made films and also recorded the voices of the farmers. By listening intently to the small voices, universal stories can come to the surface. This process can also support people in remembering things.

You also ended up researching cattle in other parts of the world, right?

Yes, after my

project on cattle in Mishima, I became very interested in the history of animals and their connection to our culture of life. During my travels in Europe, I ended up in a small village in southwestern France where I met an older lady who worked with wool. She told me that the demand for wool had been declining since it had been replaced by cotton and synthetic materials. She saw her way of living as a counterbalance to modernization. From this encounter, my short film

Nostalgia, Amnesia

(2019) developed. I took inspiration from the storyline of Haruki Murakami’s A Wild Sheep Chase, a novel about a search for meaning in a modern, disconnected world. For this film, I also researched a mountain range in the Basque region of France, where pastoral culture carries on, and the area of Sanrizuka in Narita City, Japan, which was caught up in the vicissitudes of modernization.

What was one of the things that surprised you most during this project?

I found out that the Japanese government had imported sheep to produce wool for military uniforms needed during campaigns in cold regions, such as the Sino-Japanese War (1894) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904). However, now that the use of wool is less urgent, its value has declined. For my film

Nostalgia, Amnesia, I documented an organic farmer working right next to the airport in Narita, east of Tokyo. This place used to be Japan's first sheep farm, established by the government. The airport, looming in the background, serves as a metaphor for our fast-paced society; we want things quickly and in large quantities. In contrast, you see the farmer picking vegetables by hand, one by one.

How was the response of people to your film?

I feel grateful to show these images to audiences because stories like this are no longer covered by mass media in Japan. Many people were surprised by the contrast, as such situations are rarely shown. The film ended up being 45 minutes long, so it’s not a short movie, but I noticed that even in the context of an art exhibition, many people watched it till the end. I always try to speak with the people who watch my work because I want to learn if—and how—it impacts them.

Your work often involves deep engagement with people and their personal stories.

Yes, for me untold stories are important because they can shed light on aspects of history that are often less emphasized in mainstream narratives. This is also evident in my video installation

Water Mirror.

For this project, I interviewed two older women in a rural area of Chiba Prefecture, east of Tokyo. The installation combines their voices with images of water, reflecting the fact that they live alongside a river.

"Traditionally, men tell the stories, and thus shape the narrative

of how things went."

It’s important to note that in Japan, women from older generations, especially in rural areas, rarely speak about their own history. Traditionally, men tell the stories, and thus shape the narrative of how things went. Through my conversations with these women, I offered a space for them to reclaim parts of their history, even if just in small ways. In Japan, when women get married, they often move to their husband’s family, leaving a lot behind. That can be really painful. I felt strongly that these women needed a space to share their stories. They talked about how hard their lives were, especially the challenges of farm work. One of them shared that, when she got married, her mother advised her to stay quiet and not express herself at home. It was advice that reflected the norms of her generation, but it speaks to how much women were expected to suppress themselves. Even now, I feel like there’s still a long way to go for women in Japan to achieve true equality, even in larger cities.

In the project you just described,

Water Mirror,

you blend documentary techniques with video installation. Do you plan to continue exploring this combination in your future work?

Yes, I have two ways of creating work that are important to me. I started with video installations, but my experience as a projectionist in Yamaguchi was a turning point. It was then that I began to bring in more documentary elements. Often, when people see these different practices, they don’t realize they are by the same artist. This approach works well for me because it allows me to present a subject in multiple ways, giving the audience a more layered understanding of it.

Where can we see your work currently on display, and will you be there too?

Right now, my solo exhibition is at the

Japan Foundation

in Sydney, Australia, running until March 1st. I was there during the setup, but now I’m back in Japan. At the moment I’m based in a rural area about 90 minutes outside of Tokyo. It’s quiet here, but I’m still connected to the city, and I think that balance is reflected in a lot of my work. I’m curious to hear people’s reactions to my exhibition in Sydney, especially because it’s placed in a different context. The conversations and exchanges that happen around my work are what I find most valuable.

Tender Moon, 2021, Video projection, 18'32"

Water Mirror, 2022, Video projection on bleached cotton